Edvard Munch: the artist who heard nature’s scream

A Peruvian mummy, a volcanic eruption, and the hills of Oslo – how did they come together in the legend of the world’s most piercing painting?

As autumn gives way to winter and city windows start to reflect the warm glow of candles, the name Edvard Munch often comes to mind. His paintings are like bridges between mysticism and reality. They feel like an old letter, once touched, you can sense the pulse of a bygone era. And then you pause, realizing that this letter somehow speaks of you, too.

The day he was born

In the cold Norwegian December of 1863, it seemed like the winds were already howling. So much so that they tried to drown out everything: a baby’s cries, the reprimands of adults, and the whispers of ice, the child born that day would grow up knowing that life was often louder than one could bear. And he chose to make that noise visible.

Edvard Munch was born into a family where tragedy seemed almost hereditary. His mother died of tuberculosis, his sister suffered from illness, and he lost his brother at a young age – all of which left deep marks on his perception of the world. It seems that each of his canvases became a metaphor for the shadows that followed him throughout his life.

The scream of nature: origins of a masterpiece

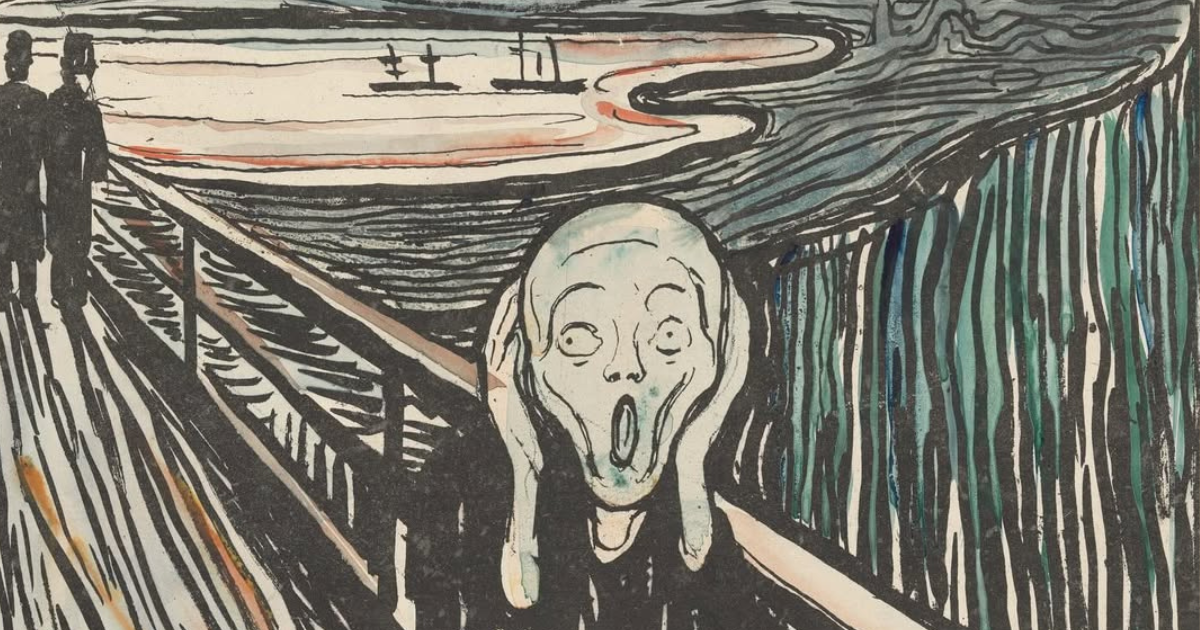

Munch often said that his paintings were his diary. And that sentiment becomes palpable when you stand before The Scream. Its endless vibration draws you in. Suddenly, there’s a lump in your throat, even if you didn’t feel anything moments ago. That’s the magic of the painting; it doesn’t ask if you’re ready to hear its story. It simply makes you stop and listen.

As the artist himself recounted, he was walking along the hills of Oslo when “the sky turned blood red, and he felt a vast, infinite scream pass through nature.” This experience became the visual embodiment of anxiety that Munch captured in the painting. But it wasn’t entirely born from his imagination. In 1883, the Krakatoa volcano erupted in Indonesia, its aftereffects causing unusual sunsets and atmospheric phenomena that were visible even in Norway.

Another source of inspiration was a Peruvian mummy Munch saw at an exhibition in Paris. Its contorted posture and expression of anguish directly influenced the central figure in The Scream. Add to this the cries from a psychiatric hospital near his home and the sounds of slaughterhouses, and you get the full environment that birthed this masterpiece.

All these elements – the blood-red sky, the surrounding sounds, and museum imagery, merged into a single painting that Munch called The Scream of Nature.

A rebellion against norms

Munch once said, “Illness, madness, and death were the angels that surrounded my cradle.” This honesty doesn’t shock you but moves you to the core. His paintings don’t just frighten; they make you reflect on yourself. What do we feel when we look at The Dance of Life? Envy for the carefree figures dancing or sorrow from understanding how it will all end? His art speaks of him and us.

Munch was a revolutionary in art, breaking traditional conventions and making human emotion the central subject of his work. He also experimented with technique. For example, in his prints, he used a unique method of cutting wooden blocks into parts and applying different colors to them. His innovative approaches inspired a generation of artists, including German Expressionists Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and August Macke.

Interestingly, in his later years, Munch created self-portraits that were strikingly transparent in their candor. In one, he appears surrounded by a mist, like steam dissolving into the cold. It’s not just a farewell but an assertion: even at the edge of life, he remained a storyteller speaking across centuries.

Today, Munch’s name serves as a reminder: listen to your emotions. Don’t be afraid to be vulnerable. And if the world around you feels unbearably loud, let his paintings show you how to turn that noise into art.

One can’t help but wonder: what would he say if he knew we think of him every December? Perhaps he’d smile his reserved Norwegian smile and reply, “My paintings have already said it all.” Or, who knows, he might invite you for a walk along the Oslofjord – to simply listen to the cries of seagulls and the sound of the wind.