Antoni Gaudí and not a single straight line

About a man whose fullness of feeling gave the city what is now called the soul of Barcelona

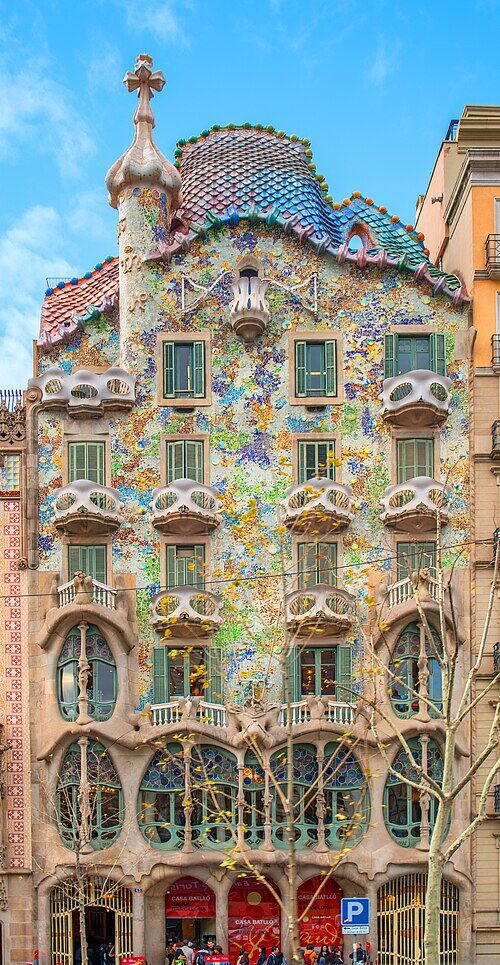

Barcelona in summer – it’s the sound of palms, thick shadows on tiled streets, and the sweet scent of dust rising from the pavement as the sun begins to set. People hurry along the narrow streets of the Gothic Quarter as if they know exactly where they’re going, each one holding in their mind the same point, a corner where everything suddenly changes. I followed them for no reason, without a goal. We turned, passed by laundry on balconies, ceramic signs, tables with water and lemon. And then we stopped. No one said anything, but everyone looked up.

In front of us stood buildings that looked like they’d been built by a child watching the sea – crooked, colorful, complex, and very simple. I suddenly remembered the taste of toffee and thought how sad it is that adults aren’t allowed to dream of sandcastles anymore.

And the thought crept in that Antoni Gaudí never aspired to greatness. He simply looked at the world with great attention and tried to build what he felt in it. No more, no less.

source: Flickr

Roots and the light in his eyes

Gaudí was born on June 25, 1852 – either in Reus or in nearby Riudoms. The debate doesn’t really matter: both towns lie in that very same Catalonia where his view of form, light, and land began. On the one hand – an industrial town with workshops and copper cauldrons; on the other, rural stillness, where the rhythm is set by sunlight, tree shadows, and the sound of crickets. In truth, both worlds were part of his childhood. His father, Francesc Gaudí, was a master coppersmith. Spatial imagination, precision of hand, and an intuitive sense of form – all of it, Gaudí absorbed at home.

His childhood was slow-paced and focused, filled with long, solitary observations: how a snail moves, how fern leaves curl, how sunlight changes the color of a stone. Rheumatism limited his body, but freed his attention. His first academy was nature itself, and he would later say, “Originality consists in returning to the origin.” His origin, without a doubt, was the Catalan land.

source: Creative Commons

He lost his close relatives early in life – his brothers, his sister, and his mother. Only his niece remained, whom he would later care for. But the experience of solitude didn’t harden him; instead, it taught him inner depth. When Gaudí moved to Barcelona and entered the school of architecture, the instructors immediately noticed his talent. Even his diploma project, which was a design for cemetery gates, was less a technical drawing than a meditation on life and death, on their boundaries and transitions.

source: public access

Streetlamps and facades

Barcelona at the time was like a canvas still holding the fading traces of a past era, while new outlines were beginning to emerge. The young Gaudí found himself in this moment of change and, instead of following the style of the day, began to search for one of his own, unlike any other. His first works – lamps, fences, furniture – may have seemed secondary, but it was in these pieces that he learned materials by touch, understood their temperaments and personalities, and began to speak with them as equals.

source: GNU Free Documentation License

It was at this time, in 1878, that his wood-glass-iron showcase at the World’s Fair in Paris caught the eye of Eusebi Güell, industrialist, patron of the arts, a man whose intuition and passion for creativity allowed him to recognize a visionary in the young architect. Their meeting marked the beginning of not just collaboration, but a friendship built on trust and a shared sense of form. Güell gave Gaudí freedom, and in return, Gaudí created parks, wineries, chapels, pavilions, and palaces. None of them resembled one another, but all were united by one thing – a belief in living matter and its infinite expression.

source: public access

But with commissions came internal resistance. Gaudí increasingly distanced himself from fashionable styles. He didn’t want to be “framed by Modernisme” – he sought his own path. He found academic symmetry too constraining, too rigid. As he famously insisted: “The straight line belongs to men, the curved one to God.”

The man and the city

Year by year, Gaudí turned further inward. Barcelona – a city of light, wine, noise, and art – was recognizing him less and less. He distanced himself from social life, shunned grand gestures, and disappeared from theaters, salons, and boulevards. You were more likely to find him on a construction site, in dusty clothes, with windblown hair and blueprints in hand.

source: Creative Commons

The young dandy in leather gloves and a silk top hat was gone. All that remained was a man in a worn-out suit and modest hat, indifferent to appearances. That was when the Sagrada Família became the work of his life. He turned down all other commissions, moved closer to the construction site, ate little, slept little, dedicating all his time to calculations, drawings, and form. People called him eccentric, a genius, a fanatic. Perhaps he was all of these things at once.

source: Flickr

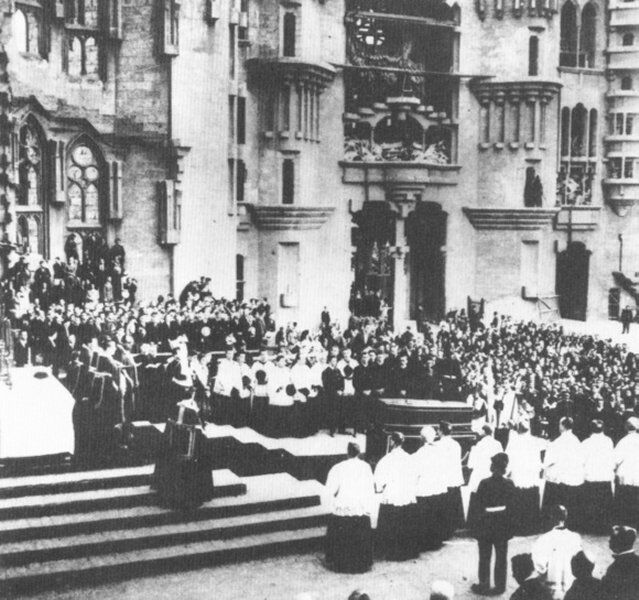

On June 7, 1926, as usual, he was returning from the Church of Sant Felip Neri. As he crossed the street, a tram struck him. Dressed modestly and without any identification, he was mistaken for a beggar. No one wanted to take him to the hospital – he was saved by chance when a priest recognized his face. But it was too late. Gaudí died on June 10.

When Antoni began work on the Sagrada Família, he already knew he would never see it completed. But that didn’t stop him. He used to say that haste is the enemy of architecture. Gaudí wanted the temple to be warm. For people not to feel like visitors, but like part of the space. And it seems he succeeded.

source: public access