Between Bukhara and the World: The Artistic Journey of Azeema Nur

How an artist from Bukhara turned creativity into a language of dialogue between cultures and generations

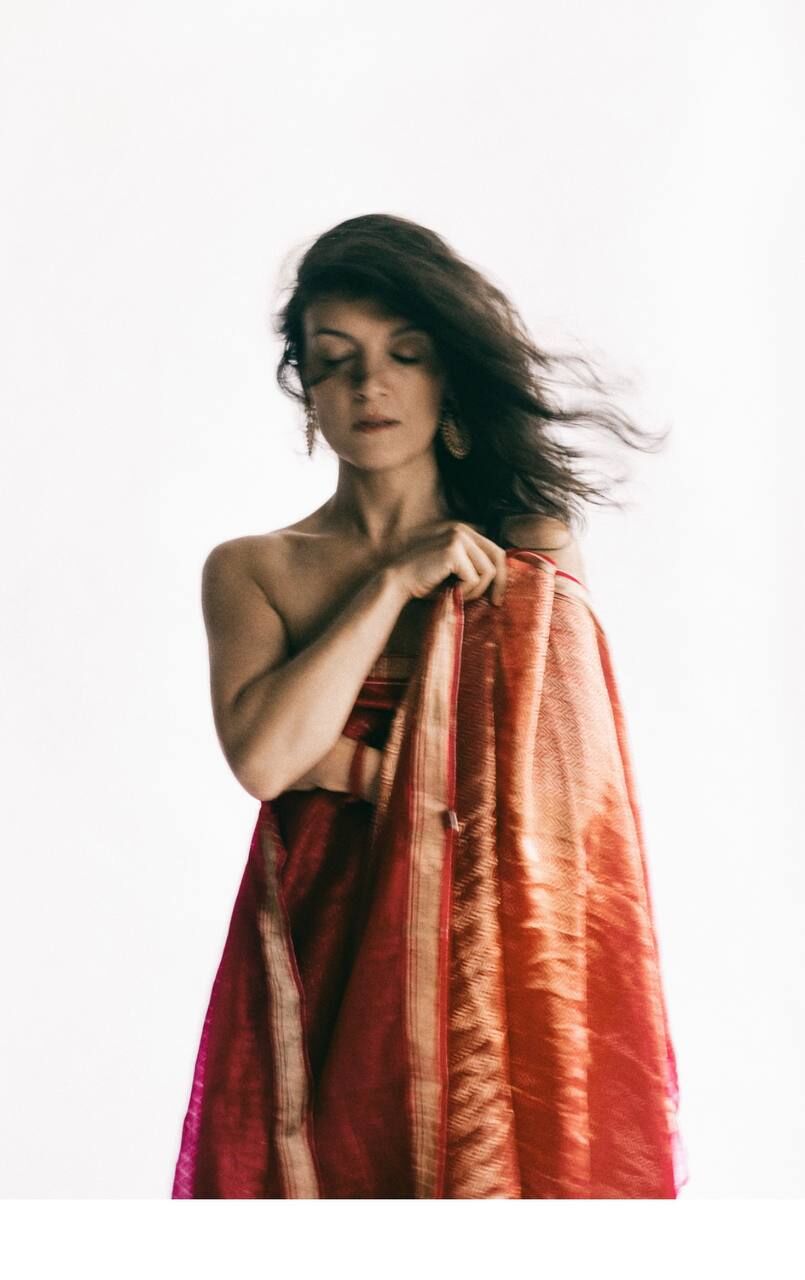

Feruza Abdullaeva, who works under the name of her grandmother — Azeema Nur, chose this pseudonym as a source of inspiration and inner freedom. The things she couldn’t dare to do as Feruza, she allowed herself to express as Azeema Nur. Her grandmother, a teacher of Uzbek language and literature, devoted her life to her students and family, though in her youth she dreamed of becoming a singer. Today, her name lives on in her granddaughter’s paintings and murals — as a symbol of intergenerational connection and a guardian of art itself.

Azeema Nur’s path in art has been as winding as her life. She studied in Bukhara, Tashkent, Paris, Mumbai, and Istanbul — exploring business, languages, philosophy, and yoga, but never academic painting. For a long time, this fact fueled her impostor syndrome, depriving her of confidence and keeping her from fully dedicating herself to art. But over time, she realized that when one is meant to walk a certain path, the universe will always conspire to help.

Photo: Mukasha Photography

ELLE: How did you come to art — and specifically to creating murals?

I was incredibly lucky to be born and raised in Bukhara, a mystical ancient city where the intricate brickwork of architectural monuments, the old courtyards, intricately adorned walls of the old Bukharan houses, and the delicate patterns of gold-embroidered velvet and silk suzani became my first teachers. I was surrounded by this ancient beauty from the moment I was born.

For me, art has always been a form of meditation, a way to dream, a source of strength — my spiritual home and my only religion.

I came to murals quite unexpectedly, in 2019, after meeting Indian artist Shilo Shiv Suleman and being invited to become an ambassador for her organization, Fearless Collective, now Fearless Foundation for the Arts. There, art became not only a language of self-expression but also a tool for engaging with the world — through collective dialogue and mural creation, where we dream of a better, more just future on the walls of different cities, always in collaboration with NGOs supporting vulnerable communities.

Photo: Sathvika Anantharaman

ELLE: Tell us about your first mural — what was the message behind it?

My first murals were two collaborative projects that still live on the walls of the city of kings — Jaipur, India. They were created together with the first cohort of Fearless Collective ambassadors.

So I consider my first true mural to be a solo work created in Mumbai in September of last year.

It appeared on the 80 ft tall wall of a residential building in the Chembur neighborhood of Bombay , within a slum rehabilitation project. The mural was created in collaboration with the NGO Awaaz-e-Niswaan, which has supported women affected by domestic violence for over thirty years.

At the center of the composition are three women of different generations sitting side by side. The woman in the middle holds a real, giant mirror — built directly into the wall — as a symbol and reminder that every woman’s greatest protector is herself.

When sunlight hits the mirror, the entire neighborhood transforms: the mural bursts into light, turning into a magical portal to a safer, brighter future.

The title of the mural came from the words of one of the quietest workshop participants: “Aaj suni aapni dhadkan” — “Today, I heard the sound of my own heart.”

These words became a metaphor — that every woman can be her own first source of protection and inspiration, especially when social support or external defenders (often men who failed in that role) are absent.

The mural became a symbol of strength, a reminder that the journey toward a better future begins with recognizing one’s own worth and believing in oneself.

Photo: Sathvika Anantharaman

ELLE: Why do women so often become the central figures in your works? Have you noticed how your murals affect the women who see them?

Women have always been — and remain — my muses and the heart of my art.

We live in a world where women’s voices have long been quieter and rarer than men’s, and where their strength and potential often remain unacknowledged. I grew up in a fairly conservative environment myself, so I know firsthand how hard it can be to be both a woman and a sovereign, whole individual.

By choosing women as my heroines, I become both their champion and a participant in a larger process — healing the collective female trauma and strengthening our shared belief in ourselves and our abilities.

For centuries, women have been associated with magic. We transform, protect, heal, and beautify the spaces around us — and that’s where our true power lies. Aesthetically, women are an endless source of inspiration for me. We are all objectively beautiful — true goddesses.

Photo: Sathvika Anantharaman

In Mumbai, I received messages of support from women and girls of all faiths and backgrounds — Muslim, Hindu, Dalit. For many, it was a revelation to see a woman artist on a crane, fifteen stories high, holding paint cans and brushes — a sight they were used to associating only with men. Some girls even said they now dreamed of becoming artists.

During the mural’s creation, we felt an atmosphere of genuine sisterhood: local women brought tea, watched over us, and made sure no one disturbed the process. That sense of solidarity and mutual care was unforgettable.

A similar reaction happened in Uzbekistan during the first street art exhibition in Tashkent in 2021, where both young and established women artists created posters and murals in public spaces. Women passing by would stop, talk, share their stories — and feel heard. That sense of being seen and supported was invaluable.

Art in public spaces unites people and restores dignity, giving every marginalized group the right to visibility.

Photo: Sathvika Anantharaman

ELLE: You’re originally from Uzbekistan but now live abroad. How does being “between worlds” influence your art?

I left Uzbekistan at the age of twenty and have lived abroad longer than I ever lived at home. This distance made my love for my country deeper and more conscious. From afar, I began to appreciate its beauty and uniqueness — along with its challenges.

But isn’t that what true love is? To see both the strong and the vulnerable sides — of a person or a homeland — and still love them.

Photo: Danny the Guy

Living in Uzbekistan first, then France, Turkey, USA and spending longish stretches in India, I began to feel like a citizen of the world. That experience enriched my artistic palette with the colors and myths of many cultures.

India became my second home, and its mythology deeply intertwined with my work. Yet it was this very journey that reawakened my connection to my own roots — to the forgotten layers of Central Asian culture.

That’s how I discovered Nana, the ancient Sogdian goddess of abundance, whose images survive in frescoes from Panjakent — on the border of modern Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. We know so little about the pre-Islamic beliefs of Central Asia — history erased too much. But traveling and learning from other traditions gave me the courage to reimagine Nana — as an avatar of Mother Nature.

Photo: Danny the Guy

My works weave together impressions from my travels, memories of my homeland, and my inner world. I try to reconstruct and reimagine lost myths, bringing them back into the contemporary narrative.

My art reflects my inner “borderland” — I live between countries and cultures, and it’s precisely this in-between that becomes the birthplace of my vision and my art.

ELLE: If you were to create a mural in Tashkent or another Uzbek city, what theme would you choose?

It would be a great honor to create a mural in my homeland.

In Uzbekistan, I’d like to focus on one of the most fundamental challenges of our generation — the urgent need to take responsibility for protecting and preserving nature.

Environmental issues and climate change are being discussed everywhere — and my mural could continue this dialogue in the language of visual art.

Photo: Mukasha Photography

Perhaps it would feature fantastical nature spirits, trees as symbols of connection between past and future, rivers as symbols of life itself — a kind, beautiful, and magical mural to attract both children and adults. Beauty is a powerful force — and remembering it sharpens our sense of responsibility to protect it.

ELLE: You studied the art of “Abru Bahor” in Bukhara. How did you discover this technique, and what does it mean to you — a craft or a philosophy?

I discovered Abru Bahor in 2016 in Bukhara, during a truly cathartic in my life. My family had gone through a great loss, and I returned home for two months — the longest stay since I’d moved abroad.

That’s when fate introduced me to my domla (teacher) Rakhim Khakimov, a member of the Union of Artists of Uzbekistan. His workshop, located in an ancient caravanserai, became my sanctuary. For weeks, I came there every morning — to learn, observe, create patterns, and watch stories appear on paper.

Abru Bahor — the ancient art of marbled paper, known globally as Ebru — translates as “spring clouds” (abru meaning clouds, bahor meaning spring). The name perfectly captures the process: bright spring-like clouds of color dance on the surface of water before being transferred onto paper.

Historically, this patterned paper was used in bookbinding and as decorative backgrounds for Quranic calligraphy, as Islamic art avoided depictions of living beings.

My teacher, Rakhim Khakimov, developed a modern Bukhara version of this art — fusing ancient technique with the philosophy of Sufism, deeply rooted in Bukhara’s history.

Creating the marbled paper is only the first step. The second — observation. For days, even weeks. Only when a story reveals itself in the patterns does the artist take up the brush to highlight its forms. It’s as if the paper and colors whisper messages from the universe — a process deeply aligned with Sufi contemplation.

This practice helped me ease the pain of loss. The meditative rhythm of Abru Bahor calms the mind and opens one’s eyes to the small miracles we miss in the rush of daily life.

ELLE: How can such ancient techniques be preserved and made relevant for young artists today?

This art form has huge potential for young people. Unlike academic techniques with strict rules, Abru Bahor offers complete freedom of interpretation. Everyone can see something different in its abstract forms — something deeply personal.

It frees artists from the pressure of narrative — you paint what reveals itself to you.

To make Abru Bahor more visible, we need workshops, exhibitions, collaborations. Bringing together artists from Turkey, Iran, even Ireland — where similar traditions exist — could show how this ancient art evolved across cultures.

It would highlight the uniqueness of the Bukhara version, developed by my teacher Rakhim Khakimov, proving it’s not a relic of the past but a living, evolving art form that can inspire a new generation.

ELLE: Do you dream of dedicating a whole project to “Abru Bahor”?

Yes, it’s a long-held dream of mine — and my teacher’s. He often reminds me how important it is to dedicate more time to this practice.

It’s a delicate art that requires patience and trust in the process.

Interestingly, my murals and Abru Bahor sit at opposite ends of my creative spectrum: murals demand speed and precision — every hour of crane work costs a lot, weather is unpredictable — while Abru Bahor exists outside time, unfolding only when the story is ready.

I dream of creating a new series of Abru Bahor works soon — and sharing this practice with a wider audience of aficionados and young artists, keeping the tradition alive.

ELLE: What challenges or resistance have you faced along your journey?

Like any artist, I’ve faced both ease and struggle. One challenge has always been balancing motherhood and creativity — art needs space and silence, which are rare when you’re a mother of two and an immigrant without family nearby.

Another challenge lies in the values of today’s world, where art is often measured by its market value. Artists face the pressure to earn rather than to simply create.

Photo: Sathvika Anantharaman

In Uzbekistan, street art is still young and sometimes met with distrust. For instance, I wasn’t able to realize a mural about supporting women survivors of domestic violence in Tashkent — local authorities refused permission, considering the theme “too negative.” Yet the sketch was vibrant and life-affirming.

Still, I believe that what seems like resistance today can become the door to change tomorrow.

ELLE: Have any of your murals been altered or painted over? How do you feel about that?

The nature of street art is ephemeral — its value lies not in longevity but in emotional impact and dialogue with society.

There’s a philosophy in that: nothing lasts forever. Carpe diem. Don’t cling — love freely. The purpose of street art is to speak when the moment demands it.

Photo: Sathvika Anantharaman

Murals typically “live” about five years. None of the ones I have been involved with have been vandalized, but my street posters — created using wheatpasting technique— have been. In San Diego, one was scribbled over with markers; another, depicting a woman in a veil, was torn down after four months.

But I still see that as a victory — a sign that the work sparked emotion, provoked thought, started a conversation.

ELLE: What are you working on now?

I continue to collaborate with Fearless Collective, which has grown into a full-fledged foundation. This winter, we’re creating a collective mural in Kochi, India, during the Kochi-Muziris Biennale — one of the most respected art events in the region.

Photo: Bobur Alimkhodjayev

I’ve also started a personal project dedicated to goddess symbolism in the lost mythology of Central Asia — to revive and reimagine the images erased by history.

In addition, I recently received a grant from Fearless Foundation for the Arts to create a new climate change themed mural in New Delhi — my largest project yet, twice the scale of the one in Mumbai. It’s both an honor and an exhilarating challenge.

ELLE: How do you see the future of street art in Uzbekistan and Central Asia?

We are slowly but steadily forming a culture of meaningful artistic dialogue in public spaces. Uzbekistan is a young country — everything evolves through experimentation and the search for balance between tradition and modernity.

Important steps are already being taken: the first social murals, international art initiatives, open-air events like Andrea Bocelli’s concert in Samarkand or the Bukhara Biennale — all aiming to make art more open, non elitist, and accessible.

Photo: Sathvika Anantharaman

The strength of street art lies in its ability to unite and restore a sense of dignity to all communities, reminding us that beauty belongs to everyone.

Unlike museums and galleries, often seen as privileged spaces, street art lives among people, as part of everyday life — creating a sense of belonging and offering inspiration and healing to all.

The next step, I believe, is the rise of more socially conscious murals — addressing pressing issues and supported by public institutions. When such dialogues take place in open spaces, it means society is becoming braver, more confident, and ready for change.

I’m convinced that, in time, street art in Uzbekistan and Central Asia will move beyond decoration — becoming a vital tool of democracy, dialogue, and solidarity.