Édouard Manet and his quest for truth

«I paint what I see, not what others like to see»

Often, geniuses are misunderstood during their lifetime, only to be celebrated after death, like viewing greatness through rain-blurred glass. Édouard Manet’s story is one of living on the edge, balancing light and shadow, recognition and rejection. In every brushstroke lies pain, and in every painting echoes defiance. His art wasn’t merely color and form; it was a revelation.

He is often confused with Claude Monet, but Manet carved his own path – a rough and solitary one. Where Monet’s works became a hymn to light and color, Manet’s creations told a story of struggle against himself, against society, and against time. His life served as a bridge between eras, constructed at the cost of his health and happiness.

Self-Portrait with Palette

The birth of a genius

Late January in Paris. Rain streaks down window panes, veiling the winter city outside. Somewhere, a newborn's cry pierces the night’s stillness. Thus begins the story of Édouard Manet. Born into an affluent family, his father, Judge Auguste Manet, envisioned a legal career for his son, not one steeped in paints and canvases. But Édouard was a child who swam against the current, seeking freedom, space, and light.

From a young age, Édouard dreamt of a path far removed from his family’s rigid expectations. His father, insistent on tradition, urged him to pursue law. When Édouard resisted, Auguste proposed another path: the navy. Hoping it might satisfy his son’s restless spirit; he believed it to be an adventurous yet temporary distraction.

The sea became his first love. Its waves inspired him: the play of light on water, the motion of ships, the faces of sailors. While aboard, he created his first sketches. At the time, they were merely the scribbles of a boy dreaming of something greater. “The sea teaches you to see,” he would later say.

Heading (N 3): Seeking truth in art

After returning from his sea journey, Manet knew what he wanted. He was drawn to paint, people, and movement. With the support of his uncle, who introduced him to the Louvre and financed his early art lessons, Manet began his studies. However, traditional academic methods quickly disillusioned him. He grew frustrated painting plaster casts, realizing he craved to capture life itself. “In the studio, I feel as though I’m in a tomb,” he remarked. Instead, he sought out live models and fleeting expressions on the faces of passersby.

His early works were full of contradictions, not entirely academic but not yet revolutionary. Even then, Manet knew he wanted to paint “what he saw” rather than what society demanded. His first major painting, "Luncheon on the Grass," caused an uproar when exhibited at the Paris Salon. The public was scandalized by the juxtaposition of a nude woman among fully clothed men. Manet defended his work, saying, “I don’t idealize; I reveal the truth.” His truth was uncomfortable, even offensive, but impossible to ignore.

The Luncheon on the Grass, 1863, National Gallery, London

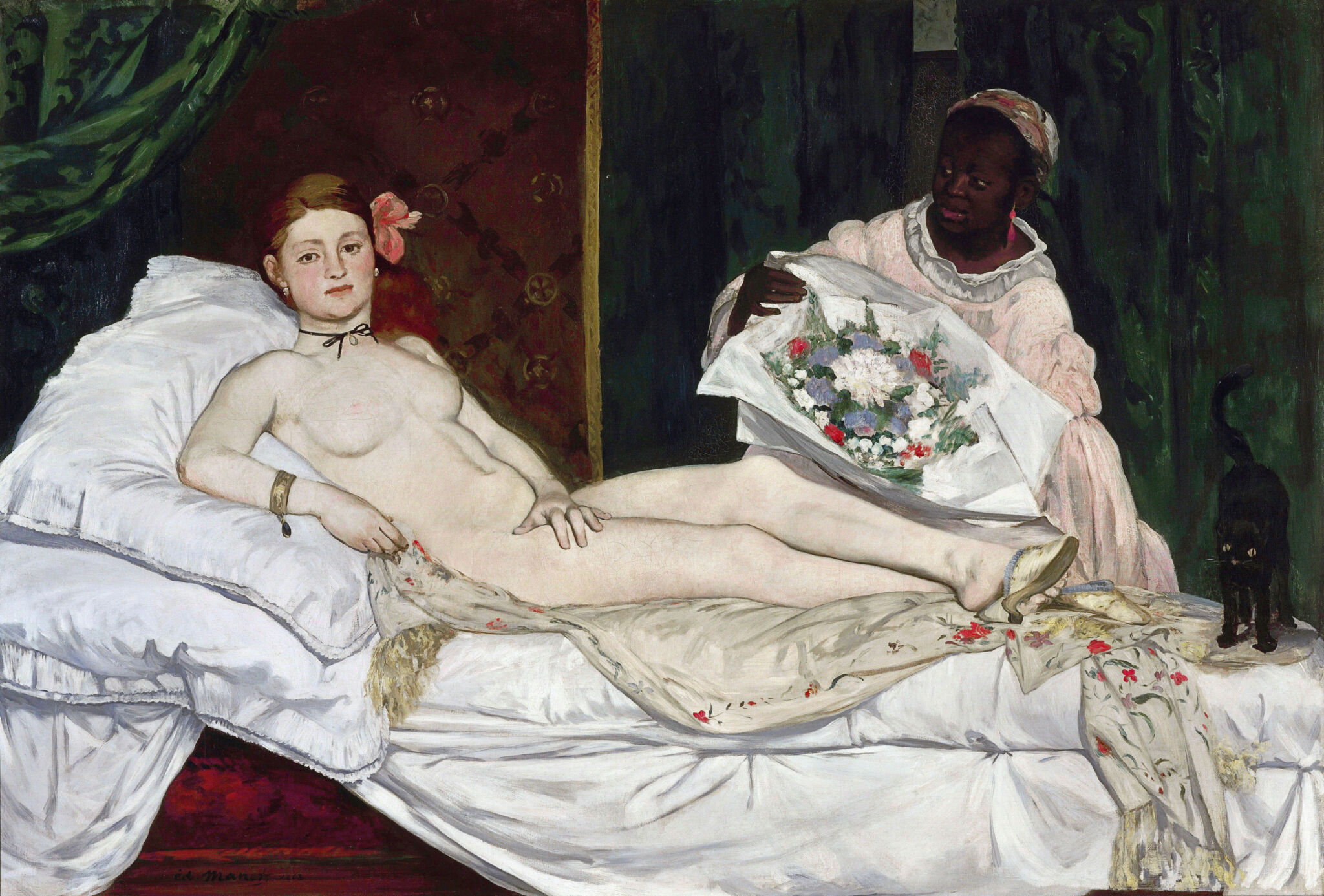

It all begins with "Olympia"

Manet was never one to compromise. One of his most iconic works, "Olympia," wasn’t merely a painting of a nude woman, it was a mirror reflecting the essence of its time. Her pose and gaze exuded independence and audacity. Critics attacked the painting, calling it vulgar, but in reality, they feared its frankness.

Inspired by Titian, Manet’s "Olympia" was no mythological Venus. She was flesh and blood, a living, breathing woman. She became a symbol of a new era, though her contemporaries weren’t ready to embrace her. Olympia wasn’t just a painting; it was a provocation, a dialogue with the future.

Manet’s battles weren’t confined to the canvas. His body became a battleground, plagued by rheumatism that tormented him for years. Despite the pain, he painted, worked, and persevered, never surrendering. “Each painting is my life,” he once said.

Shortly before his death, Manet was awarded the Legion of Honor – a recognition he had long sought. Yet fate was unkind: eleven days later, after undergoing a leg amputation, he passed away. He left behind a world just beginning to grasp his genius.

A legacy that lives on

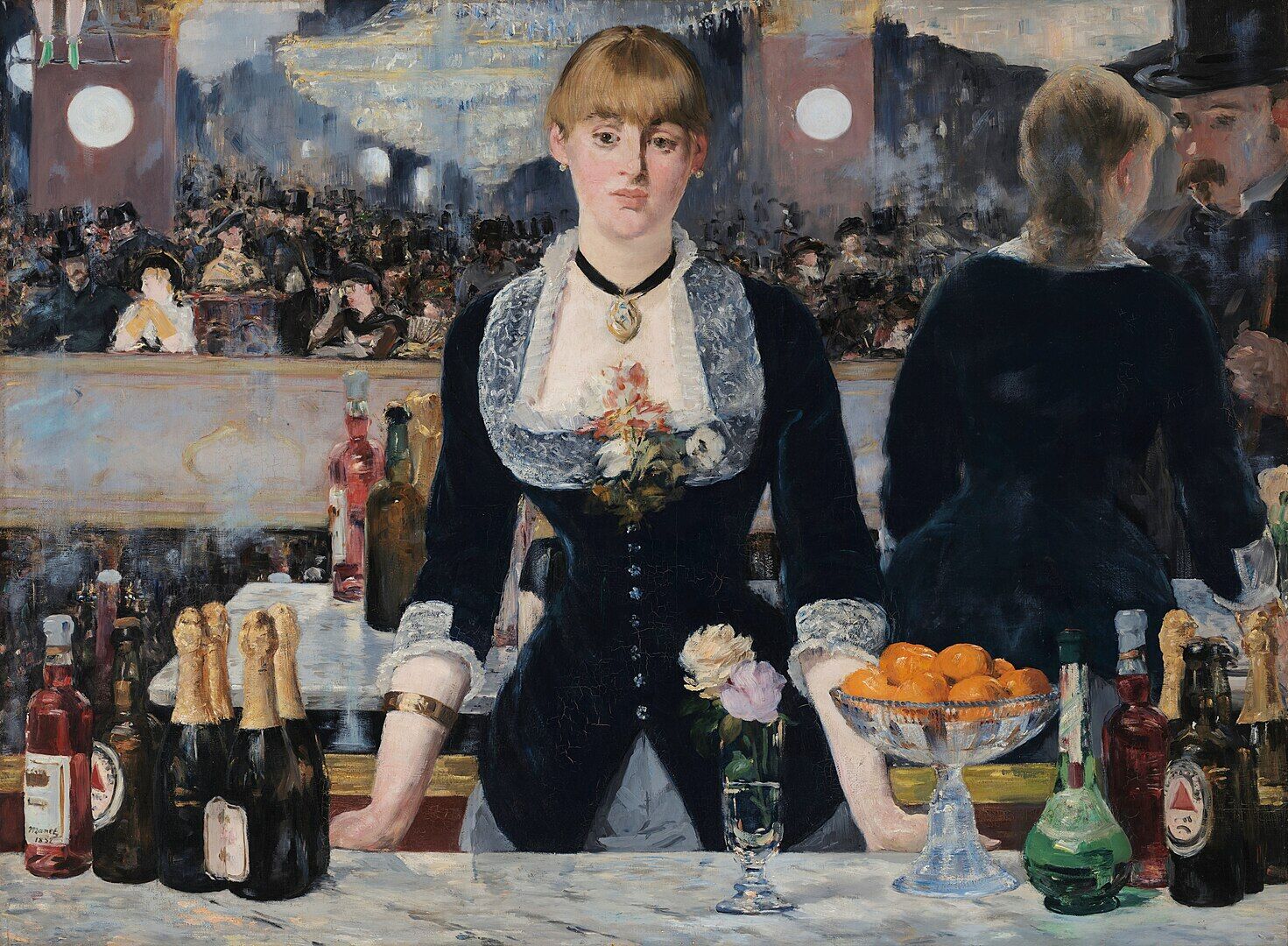

A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1882, Courtauld Gallery, London

Today, Manet symbolizes freedom. He laid the foundation for a new perspective in art, dismantling the barriers between academia and reality. Works like "A Bar at the Folies-Bergère," "Luncheon on the Grass," and "Olympia" each tell a story, raw, real, and as he saw it.He left behind a world where art was no longer confined by rules. Édouard Manet proved that true beauty lies not in ideals but in truth. And it is this truth that has immortalized his name, for truth resonates in all of us.