Mary Cassatt

An American in Paris, a timeless artist, Degas’s ally, and the enduring voice of motherhood in painting

Impressionism is often associated with the lightness of French life – carefree picnics and the airiness of midday shadows. But American painter Mary Cassatt turned this familiar world upside down, becoming a symbol of a new sensibility. Her canvases radiate with the warm glow of family hearth, sincere emotion, and deep feminine wisdom, where the everyday is elevated to high poetry.

Home

Mary Cassatt was born on May 22, 1844, in the city of Allegheny. Her future seemed preordained. The daughter of millionaire Robert Cassatt and the educated aristocrat Katherine Johnston could have become a carefree socialite, spending her days in salons and accepting offers of advantageous marriages. But from an early age, Mary displayed a rebellious spirit that would shape her life. During a trip to Europe at age eleven, she encountered the works of great artists and told her parents with resolute certainty that she would dedicate her life to art, despite their objections.

"I don’t want a dress and a fan, I want a brush and paints!" she firmly told her mother.

source: Princeton University Art Museum

Stubbornness and ambition were part of her nature. Mary insisted on studying at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, defying the puritan norms of American society. “Girls only attended classes three times a week. We were seen as amusing creatures, incapable of creating great art,” the artist later recalled. But this only strengthened her determination.

See Paris and die

The Paris that the young artist longed for turned out to be a harsh test. Despite its openness to new ideas, the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts was closed to women, and cafés where the bohemian elite gathered didn’t admit unaccompanied ladies. Yet Mary didn’t give up. She regularly visited the Louvre, copying old masterworks and taking private lessons, sharpening her technique and forming her own artistic vision. She managed to have her works accepted into the Paris Salon exhibitions, though critics were not always kind, and she was not fully accepted, as a woman and a foreigner.

source: Smithsonian Institution Archives

A turning point came with the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War. Finding herself in a creative and spiritual crisis, Mary returned home. But fate offered her another chance: the Archbishop of Pittsburgh commissioned her to make copies of Italian masters. These travels not only returned the brush to her hand but also introduced her to people and ideas crucial to her art.

Edgar Degas and the alliance of rebels

In 1874, Paris was buzzing with an artistic revolution. At the Impressionist exhibition, Mary saw the works of Monet and Degas for the first time. “Their paintings are air, they are life,” she wrote to a friend. When Degas saw her paintings, he was captivated. Their acquaintance changed both of their lives. Mary joined the Impressionist circle, becoming the only American ever welcomed into their close-knit group.

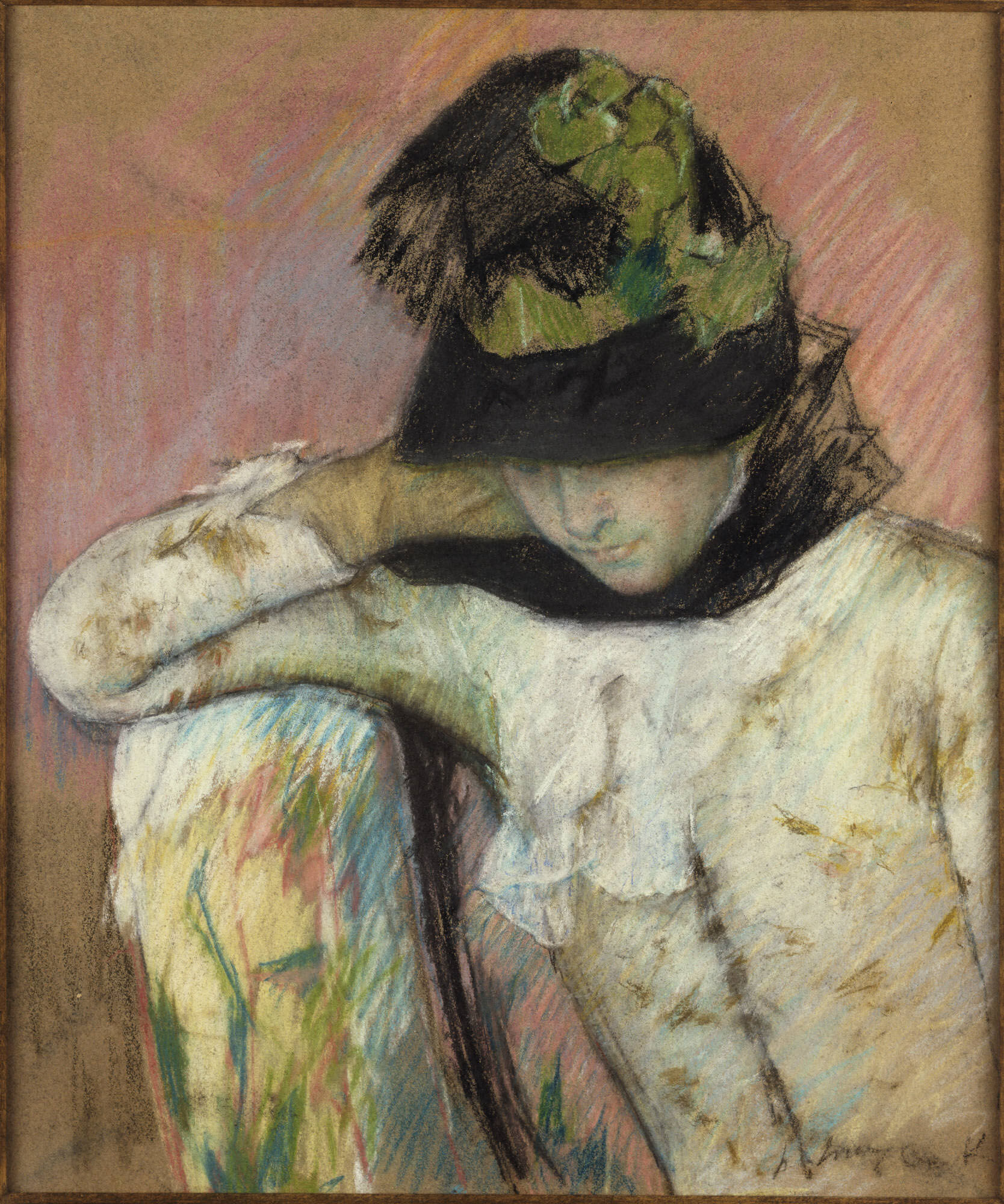

Together, they explored new techniques, particularly pastels and etching, which became central to her work. Degas’s influence is visible in her paintings – alive with movement, emotion, and delicate plays of light. Yet Cassatt’s distinct style and feminine perspective shine through: subtle, profound, and unmistakably her own.

source: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

A woman painting women

Cassatt chose the familiar themes for everyone when painting – motherhood, children, and domestic life. But her approach shattered expectations. She didn’t idealize her subjects; she portrayed them the way they were – tired, irritable, pensive. It was revolutionary for the time. Her painting “Little Girl in a Blue Armchair” (1878) exemplifies this honest portrayal. Mary captured the world of women and children with candor and dignity, elevating the everyday and making it worthy of artistic attention and respect.

source: National Gallery of Art, Washington

Her use of Japanese woodblock print elements added freshness and decorative charm. In the renowned painting “The Child’s Bath”, a simple scene becomes a work of art, capturing profound tenderness and care. This style earned her true fame and the recognition of both critics and the public.

source: Art Institute of Chicago

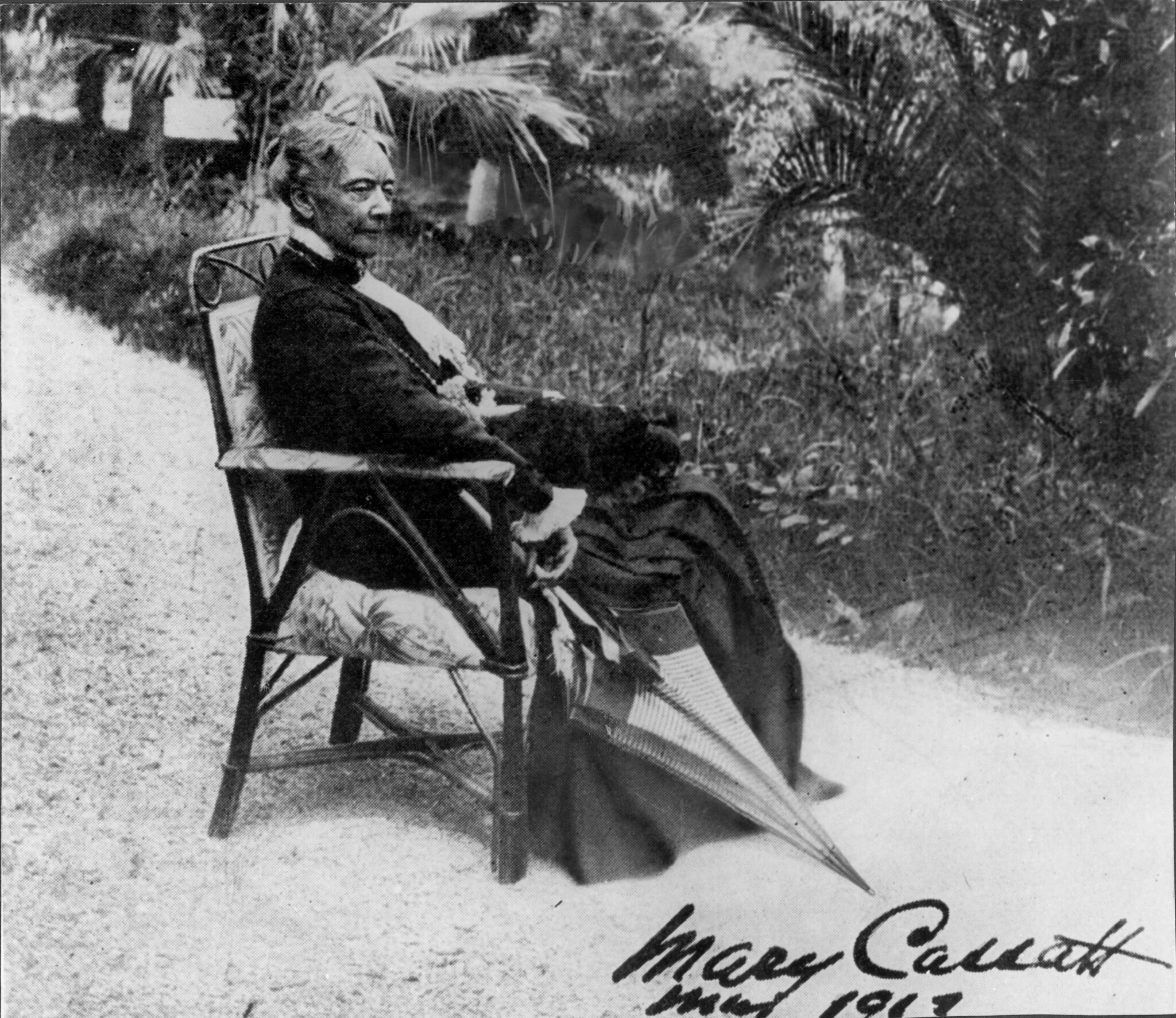

In her later years, Mary Cassatt actively participated in the women’s rights movement, organizing exhibitions and speaking out in support of suffragists. Though she gradually lost her eyesight, she remained active and courageous to the end. Her final exhibition in 1915, dedicated to the fight for women’s suffrage, was a powerful statement of her convictions and life’s mission.

In 1926, Mary Cassatt left this world, but she left behind more than paintings. She left a reminder that even in the most ordinary moments lies a depth worthy of great art.

source: Frick Art Reference Library Archives