O Beauty! dost thou generate from Heaven or from Hell?

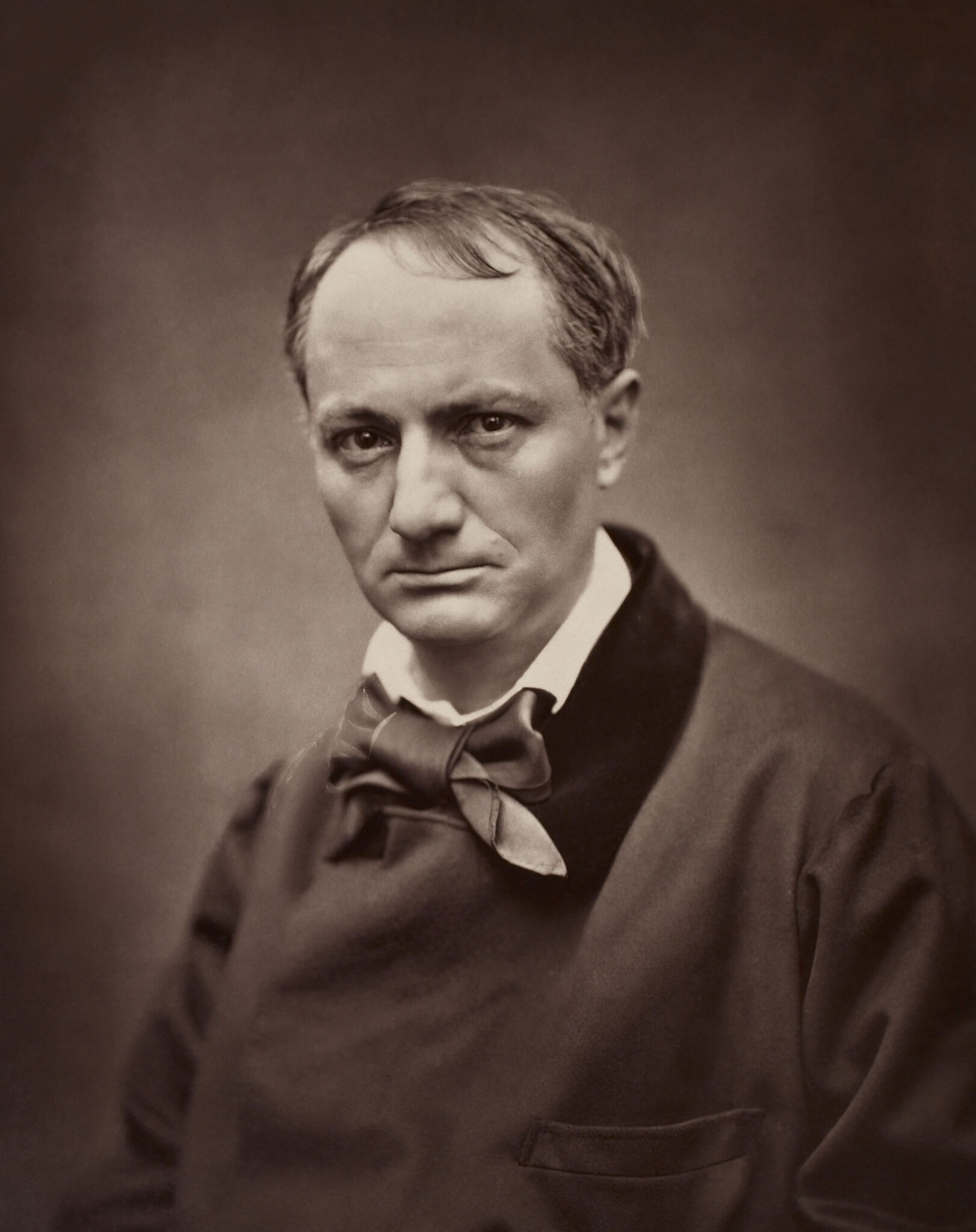

Charles Baudelaire – beauty as poison, poetry as confession

O Beauty! dost thou generate from Heaven or from Hell?

This is how «Hymn to Beauty» begins – a poem that reads like a will, a confession, a mirror in which the poet’s fate reflects. Lines as light as petals and as sharp as razors. A warning: we’re about to plunge into darkness. Into the very essence of the beautiful. Into Baudelaire himself.

A childhood marked by guilt

Death, which he longed for at twenty-four, did not come. Charles Baudelaire survived. A doctor found him, blood still seeping from the wound. But fate said no – two days later, he was sipping coffee on Place Vendôme, golden dust of unwritten verses glittering on his cuffs. Sometimes, the most tragic moments in life become prologues to great books.

As a child, they called him sensitive. But perhaps it was a different kind of sensitivity, the one that senses not heat or cold, but the shifting of reality itself: when love becomes duty, and a mother turns into a stranger. Caroline Dufays remarried a year after her husband’s death, and a new man moved in, the one who "knew how to do things right." But Charles did not. He never would.

From his boarding school, he wrote letters to his mother filled with more penitence than a saint’s journal. A small boy with an adult’s script: “You are disappointed in me... I don’t dare to pull myself together.” His whole life would seem to prove those words spoken at eleven. Laziness, bohemia, guilt. And poetry. The kind that hides in the hem of a courtesan’s dress or between the lines of a dying man’s testament.

Photo: British Library

Women and everything that’s too much

The inheritance disappeared quickly. Eighteen months. Charles – a dandy, connoisseur of wine, Parisian brothels, lace, and melancholy. His friends were painters and street philosophers. His enemies were bankers and university deans. Peace would have been a betrayal.

Where else to seek God, if not in a woman? But women in Baudelaire’s life weren’t solace – they were an ordeal. Jeanne Duval – with a body like sculpture and illness. Apollonie Sabatier – a muse, a bourgeois dream mistake. Marie Daubrun – green eyes, theatre, passion. They were symbols. Or chimeras. Women as sin and as a temple, as flesh and as phantoms. Women as the reason to die and the reason to stay alive.

Photo: Budapest Museum of Fine Arts

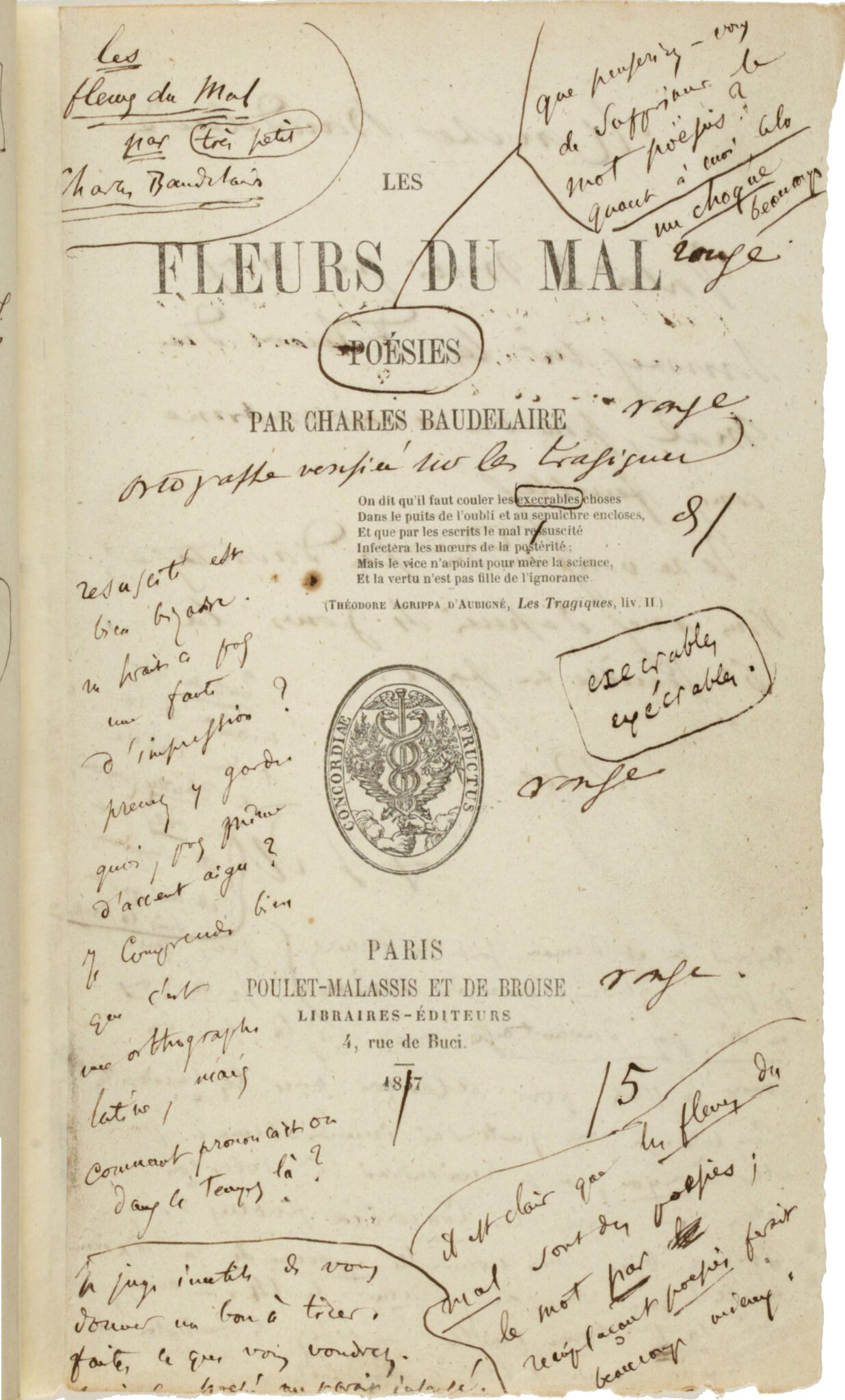

Poetry as wound and cure

Baudelaire wrote from life – not an external, but an internal hell. His “The Flowers of Evil” is a herbarium of pain, compiled with surgical precision. Here is rotting flesh, here a womb full of spiritual pus, here a prayer turned curse. He writes as if opening a wound – to heal. Or to infect.

His poem “The Albatross (L'Albatros)” reads like a self-portrait: a grand bird, majestic in the sky, clumsy on land. The crowd laughs, and the poet is silent. He does not belong to a world that lives by Saturdays and sales. He has his own calendar: days of inspiration, nights of disintegration.

Baudelaire is more than a poet. He’s a dream-state philosopher. He’s fascinated by scent, sound, and color. In “Correspondances”, he uses the word “symbol” for the first time, and from this moment, Symbolism begins. “Perfumes, colours and sounds echo one another,” he writes, and you feel he’s not speaking of senses but of doors. To something else. To the essence.

Photo: Gallica Digital Library

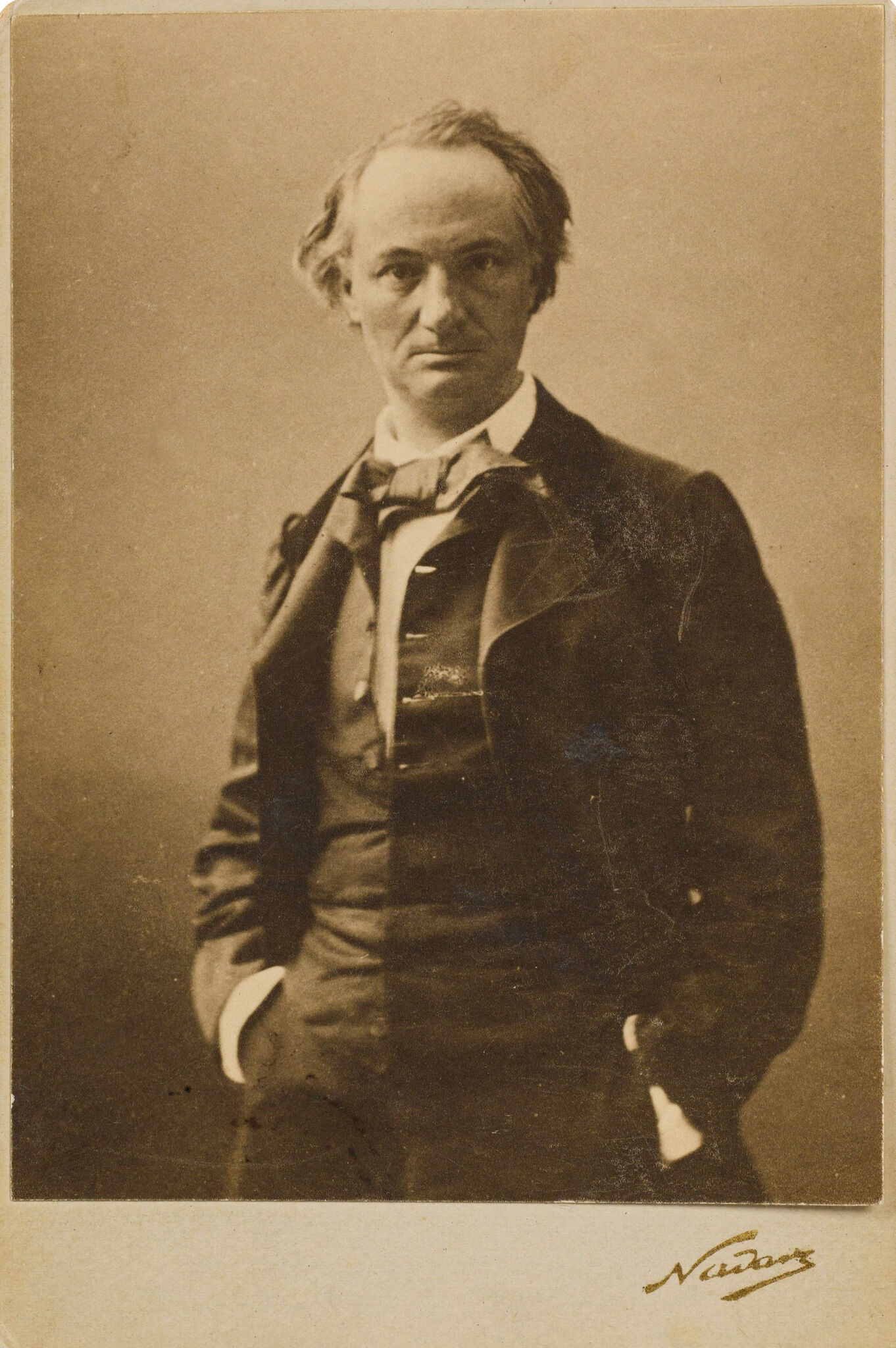

Dandyism as religion, solitude as style

He translated Edgar Allan Poe not only with words but with blood. He sensed a kindred spirit: equally restless, equally beautiful in his disdain for the banal. Baudelaire longed for prose and gave us “Paris Spleen (Le Spleen de Paris)” – miniature meditations on the city, loneliness, and meaning. None ends with a full stop.

Baudelaire’s dandyism wasn’t about fashion. It was about survival. Clothes as armor. Beauty as defiance. Green hair, Venetian coats, pale perfumed skin like a character from a novel – he hid behind the exterior to escape the interior, even for a moment.

Why does art exist? For him – to escape. To feel the air, even for a second. Like the albatross, who can only take off from the crest of a wave. On flat ground, he is helpless.

The eternal question of beauty

And whom we see is not just a man. Not just a poet. But a figure who changed continents. Symbolists, decadents, surrealists – they all began with him. Verlaine would title his book “The Cursed Poets (Les Poètes maudits),” and it was about Baudelaire. Because he didn’t just write about evil. He made it comprehensible. Beautiful. Humane.

At the end of his life, his body gave out. Paralysis, apathy, poverty. At his side was his mother, Caroline. The circle was complete. But his verses are not. They are tunnels into another era, another consciousness, other feelings.

The question Baudelaire asked Beauty “Did you come from hell or heaven? (dost thou generate from Heaven or from Hell?)”, is still ours to ponder. And his answer lies in every verse. Every image. Every "too much." Because true poetry is always too much. And always forever.

Photo: Sotheby's