The mysterious “Delphos” gown

A timeless garment

Who freed women from the corset? For over a hundred years now, the credit has been shared between Chanel and Paul Poiret. But there was another designer – Mariano Fortuny. His Delphos dress gave women the freedom to breathe, move gracefully, and look alluring and modern. Let’s take a closer look at what makes this gown so unique.

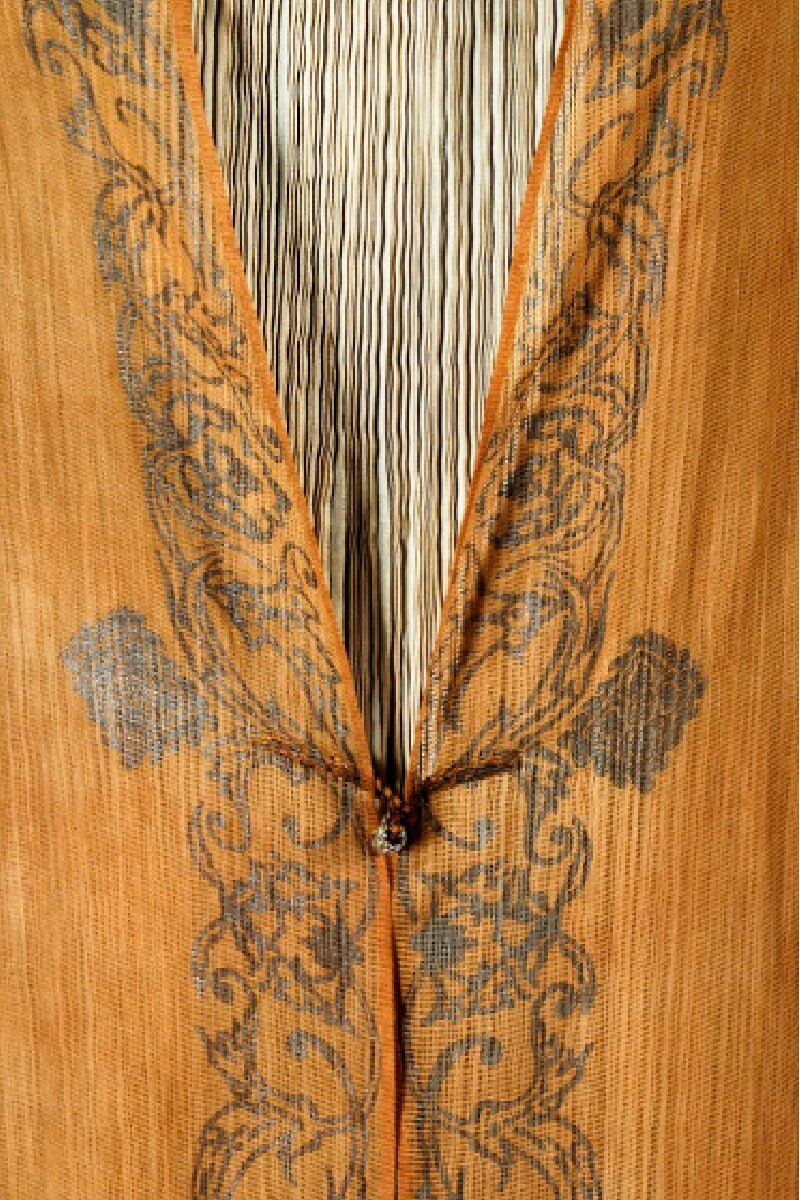

Mariano Fortuny was a Venetian designer of Spanish descent, an artist, and an inventor. His early work focused on velvet, brocade, and tapestries. He created fabrics using Renaissance-era Venetian techniques. In 1907, he introduced the Delphos dress to the public – a gown made from finely pleated silk that shimmered playfully in the light. The dress was light and airy, the fabric elegantly hugged the body, flowed freely, and allowed for ease of movement. A distinctive detail was the Murano glass beads sewn along the seams, which gently weighed down the delicate silk to prevent it from billowing. The dress could also be styled with a belt if desired.

photo: nasjonalmuseet

To say the dress was revolutionary is an understatement. After the restrictive S-curve silhouettes of the early 20th century, the Delphos was a breath of fresh air, requiring no corset. But it was also a bold challenge to social norms. The dress was modeled after the ancient Greek chiton, a type of women’s under-tunic, and in the early 1900s, that reference was seen as quite provocative. At first, women only wore the Delphos at home. Yet, as in every era, some women enjoyed shocking high society. Clarisse Coudert, Elena Sorolla García, and Isadora Duncan wore these tunic-style dresses and became pioneers of new fashions and new rules in women's attire.

It’s believed the dress was named after the ancient bronze sculpture “Charioteer of Delphi.” In the 19th century, archaeological excavations in Greece were in full swing, and the rediscovery of the ancient world sparked wonder and inspiration. Mariano Fortuny became a major proponent of Greek culture. While studying fabric production, he invented a new technique for pleating silk. This breakthrough tamed the delicate but unruly fabric. It was this very silk that was used to create the goddess-like tunic dresses that transformed women into modern-day Greek deities.

photo: fortuny visitmuve

Fashion has a subtle but important rule: a designer can claim they “invented” the mini skirt, the little black dress, or any other staple only if they have a patent to prove it. Mariano Fortuny was a savvy entrepreneur, and in 1909, he patented his invention. His pleating method remained a closely guarded secret. After his death, documents were found revealing only a few steps of the process. The full method remains a mystery to this day. However, the archival research was not in vain: scholars uncovered photographs, letters, and the patent application itself, which listed Henriette Negrin, Fortuny’s muse, wife, and creative partner, as the true inventor. Fortuny was only the patent holder. Henriette, a French designer, created fabrics and garments alongside her husband, and after his death, took on the task of cataloging his work. While Mariano received fame, books, and accolades, it wasn’t until researchers began studying the couple’s archives.

photo: nasjonalmuseet

A dress with such a mysterious history gained widespread popularity, as archival photographs show, after World War I. Women began to enjoy greater personal freedom, and the gown perfectly reflected the spirit of the era. It was also practical: the dress could be stored folded like a bundle, making it compact and travel-friendly. And one more undeniable advantage: after being stored this way, it would immediately return to its original shape.

photo: cultura.gob