Away from home

Three women who promote Uzbek cultural identity while living abroad

These representatives of modern society live and work abroad but continue to honor Uzbek culture and communicate with the world through their creativity.

Aziza Kadyri – a multidisciplinary artist working with performative art and augmented reality, co-founder of the Qizlar collective. Country of residence: United Kingdom.

photo: Ekaterina Timko

The path to the profession

Now, I call myself a multidisciplinary artist, but it wasn’t always like that. My path to the profession was quite winding. Since childhood, I’ve always loved drawing, creating stories, and building worlds. Instead of playing on the playground, I would draw all over the ground in front of our house.

As often happens, my family believed that art should remain a hobby and that I needed a “real” job. So, I didn’t immediately pursue art professionally. I enrolled in diplomacy, but soon dropped out and moved to China, choosing the much more creative profession of a fashion designer. Then I got into theater and started working on costumes, and later, scenography.

My interests shifted for two reasons: curiosity and external circumstances. Curiosity drove me to study 3D programs, create installations, and experiment with performances. External circumstances, like the pandemic, forced me to explore new directions. I finished my master’s degree at Central Saint Martins in 2020 when the pandemic began. As a result, when I graduated, I couldn’t work in my profession, so I decided, driven by my curiosity once again, to learn about augmented and virtual reality and immersive technologies in general. Now, I actively use all the knowledge and experiments I’ve accumulated over the years in my artistic practice.

Uzbek Cultural Code in art

The brightness and ornamentation inspired by Uzbek embroidery only appeared in my work a year and a half to two years ago. It all started with my project “9 Moons,” the centerpiece of which is a textile installation. This project inspired me to study the art of embroidery in Central Asia, as it is based on the half-lost dowry of my great-grandmother—a vintage embroidered cloth from the Jizzakh school of suzani. After that, I delved deeper into the visual language of ornaments and began working with them in dialogue with technology and artificial intelligence. Many visual solutions in my work reflect the hybrid, syncretic images I grew up with abroad, making them a product of a kind of diasporic lens.

In each country, due to differences in context, the reaction to Uzbek codes is always different. I can speak a bit about the UK: unfortunately, there is very little knowledge of Central Asia here, and when people see my work (and my appearance), many associate it with a more familiar region to them—Mexico and Central America. That’s why social media is important to me as an educational channel, a platform to increase the visibility of voices and culture from the region. For example, I share my research for projects on my Instagram page, and it has become a great opportunity for my English-speaking followers to access knowledge about Central Asian culture, which is usually inaccessible to them due to the language barrier.

About creative vision

My artistic approach is based on collaborative and interdisciplinary methods, through which I create both physical and digital immersive experiences. In my projects, I explore themes of migration, social invisibility, identity, decolonization, feminism, and the loss of language. I’m interested in the potential of XR/AR/VR and AI technologies in the context of artistic research and social practices. I also explore new ways of working with cultural heritage, especially textiles and costumes, crafts traditionally considered “female.” By using modern technologies, I reinterpret traditional narratives, making them relevant for today, and weaving modern stories and alternative mythologies.

About inspiration

When I plan projects, the narrative or intellectual component is just as important as the emotional aspect—how the viewer will perceive and experience the project phenomenologically. It’s easier to achieve this goal if I know from my own experience what made me feel certain emotions or memories and how to recreate them in an exhibition space. Therefore, I often draw inspiration from personal or family stories, discoveries, and internal upheavals.

My source of energy is likely my endless optimism (inherited from my dad) and an excessive sense of responsibility (passed down from my mom). I also love interacting with people and working in collaboration or with different teams. Even in inevitable disagreements, a spark of something beautiful is born.

In Venice, when presenting our exhibition at the Uzbekistan Pavilion with Qizlar, I met artists Mounira Al Solh (Lebanese Pavilion) and Manal AlDowayan (Saudi Arabian Pavilion) — they have wonderful projects, as does the Egypt Pavilion led by Wael Shawky. I enjoy art that isn’t afraid to be playful or even fantastical at times, like the sculptural costumes by Daisy May Collingridge. I love the theater company called Peeping Tom. I could go on and on with names...

About London

I’ve lived in and grown up in large metropolises my entire life, and I can’t imagine living outside of a big city. London attracts me with its rich cultural life, career opportunities, and access to invaluable educational resources. The saying “If you want to live, you have to hustle” is spot on for this city. Living here is not easy; London loves to test your resilience. This keeps me on my toes, motivating me to always learn something new and not stay in one place.

About color

For many years, at the beginning of my artistic journey, I didn’t feel comfortable using color. It was difficult for me to understand how to incorporate color into my work. Even my graduation fashion collection consisted exclusively of gray and beige tones—I focused on creating textures rather than experimenting with color. But perhaps I was under the influence of the so-called “fear of color in Western culture.” I somehow believed that using a lot of color wasn’t the “right” way to express myself.

After a long journey of accepting my heritage and identity, I’ve learned to appreciate the brightness of Central Asian art, which manifests in all aspects of life. Now, I can’t imagine my artistic practice without the visual richness that always surrounded me at home (even in migration), including the diverse textiles, carpets, and ceramics. It’s been a liberating adventure to recognize the value of these art forms, which I had unconsciously ignored for a long time.

Guzal Said is a baker with an architectural background and Le Cordon Bleu alumna, an innovative chef, co-founder of the Registan café-bakery in Riga, and a creative mind behind ButterDinnerClub. Country of residence: Latvia.

photo: Sasch Fjodorov

The cult of food

In our family, all meetings and events revolve around food. We always have a “menu” planned, even for the most ordinary Sunday family day at the dacha. It seems that it was inevitable for me to turn to culinary arts as a profession.

Technically, I have been working in this field for five years, and I stumbled into it quite by accident, asking my boss if I could work in the kitchen of the restaurant where I was employed in the marketing department.

I completed a boulangerie course at Le Cordon Bleu, but I don’t believe this school offers much beyond solid technical skills. However, it holds a special place in the culinary world, with a reputation that speaks for itself. My grandmother taught me Uzbek cuisine. She worked a lot with dough and could roll it out to being incredibly thin. My father taught me how to make plov and continues to teach me. To me, it’s a “masculine” dish, especially when it needs to be prepared in large quantities.

I don’t have to incorporate the Uzbek cultural code into my work consciously; it naturally exists through the spirit, presentation, and hospitality of all my projects. Once, I witnessed the entire process of making Uzbek meat porridge (halim, halisa).

Watching two men stir wheat with meat using wooden sticks for several hours was something remarkable. I often wondered who invented this dish and how.

Uzbek cuisine in Latvia

Latvia can hardly be called a foreign audience. We are very different, but we have much more in common than it seems. For example, we all love plov and samsa. I think it’s hard not to love Uzbek cuisine. It’s rich in carbohydrates and fats, so you’d have to try very hard to make it unappetizing for guests.

Most challenging and memorable projects

In a short time, I’ve had the pleasure of working with brands like Range Rover, Rolls Royce, Bang & Olufsen, Pernod Ricard, Aquazzura, and others. Working with them was incredibly rewarding. My favorite project in terms of beauty was creating buffet tables for Vetrina Tashkent with the presentation of Aquazzura tableware. I was also deeply inspired by a project for Bang & Olufsen in Riga, where we created an immersive ASMR room.

The most challenging projects are private events (birthdays, family celebrations), surprisingly. We take them on only in exceptional cases.

Non-culinary interests

My love for cars stems from my passion for design, functionality, and the human drive to evolve and develop technology. You can observe all of this in automotive design history, and it’s nothing short of fascinating.

In my free time, I enjoy long walks through the forest and by the sea, spiritual practices, studying history, and reading good books. I work a lot, so in my free time, I do everything to stay in good spirits and shape.

Other goals

I don’t want a traditional restaurant, at least not right now. It would feel like “a marriage of convenience,” settling down when I’m not ready for that. Opening a studio, a culinary lab—yes. I’m working on it.

A Michelin star is not my goal. Overall, starting a business solely for awards is a bad idea. I think we place too much importance on that, just as we do on culinary education.

Culinary Philosophy

Food brings people together. I see it as a process, from the initial thought to the act of savoring. The process of having lunch or dinner is freedom and the courage to be yourself. Cook what you want, eat how you want. Of course, there are rules of etiquette and preparation, but they can be broken if you know how. Food is enjoyment and a sense of security; that’s how it should taste. You can influence people through food, just like any other art form. My task is to create beauty that grounds people.

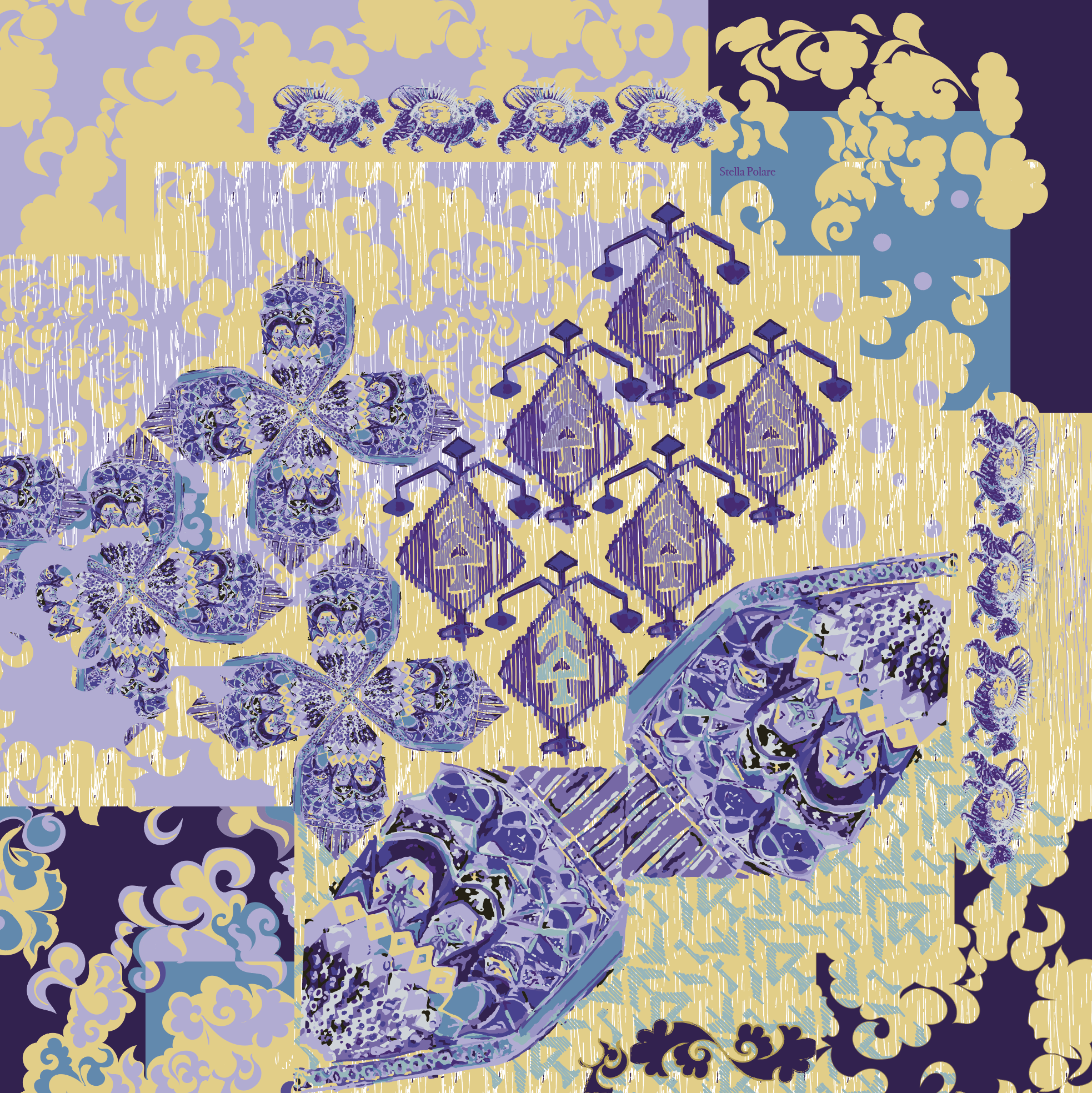

Khulkar Yunusova (Stella Polare) – a Franco-Uzbek contemporary artist who creates silk scarves with unique illustrations. Khulkar’s major projects have been exhibited at UNESCO, the Louvre, and the Jacques-Coeur Palace. Country of residence: France.

photo: Stella Polare

The path to the profession

After studying economics and management, I worked in the pharmaceutical industry in France for seven years. My last project in pediatric oncology in the late stages made a huge impression on me. Visiting hospitals and observing children with cancer showed me that life can be completely different. The young patients, physically fragile yet spiritually mature, made me reflect deeply. The slightest relief of pain for these children brought joy. It was at that moment that I realized I wanted to dedicate myself to art. Art became my guiding star, hence my artistic pseudonym, which is also a tribute to my grandmother, as “Khulkar” translates to “polar star.” I am a Franco-Uzbek interdisciplinary artist. I work with drawing and painting, photography and video, performance and installation, graphic design, and textile art, as well as culinary arts. My work is dedicated to the concept of “vitaculture”—the urgency of joy. In my practice, I explore the boundaries of human relationships, feminism, the interaction between East and West, themes of memory and death, and the mythology of the French letter “H.”

Stella Polare

Uzbek Cultural Code in Art

For me, the Uzbek code is part of my personal identity as someone who grew up in a Uzbek family with strong traditions, the significance of which I only fully understood after moving to France. I began working with Uzbek prints in 2019, the year I created the “Motifs of the Uzbek Soul” project. The Uzbek national ornament is an incredibly deep and elegant practice, possessing an original harmony of form and color. Each motif carries a special sacred meaning for me—sometimes healing, sometimes protective, and sometimes a wish for prosperity and well-being. I associate these motifs with the taste of childhood, the smell of landscapes from my homeland, the voices of grandparents who send me off to exams or other important events with touching blessings, “fotikha” and “duo.”

Today, I continue to work with Uzbek prints within the Stella Polare Scarves line. A scarf is a special accessory for me; it emphasizes freedom in self-expression through clothing. In Europe it is a symbol of status, in the East, it is a symbol of female emancipation. Therefore, the reason people wear scarves and how they do so is, for me, a matter of freedom and belief. The main thing is for each person to do it in harmony with their own views and decisions.

Art that reflects Uzbek culture resonates abroad for several reasons. First of all, Uzbek culture is unique and exotic for many people outside Central Asia. National patterns, bright colors, intricate ornaments, and traditional motifs attract attention with their original harmony. Secondly, cultural diversity is always valued in the art world. Many people abroad appreciate the opportunity to learn about another culture through works of art. My work often sparks curiosity and a desire to learn more about the history, traditions, life, and contemporary art of Uzbekistan. Furthermore, universal themes like love, family, human relationships, feminism, memory, and death, present in Uzbek art, resonate with people from different countries and cultures. These themes are understandable and relatable to everyone, regardless of their cultural background. I’ve noticed that the longer I live in France, the more I feel that the French are increasingly similar to Uzbeks. This subjective observation only strengthens the connection between our cultures, making Uzbek art even more attractive and understandable to the French audience.

Stella Polare

About Paris

Paris, for me, is a Great School and a Great Garden.

My move to Paris in 2008 was made possible by a scholarship I won, allowing me to continue my studies in management and administration. This was a huge opportunity to broaden my horizons and gain new experiences that helped shape me not only professionally but also personally.

Moreover, Paris is a Great Garden where everything buzzes with life. It is the world capital of art, science, and culture. Here, an immense number of museums, galleries, and events provide unique opportunities for networking, self-expression, and consequently, professional growth. All of this creates an incredible creative energy that enriches the city’s history. Living in Paris has opened doors to new collaborations and allowed me to meet other artists, critics, and curators.

Stella Polare

About plans and the French letter "H"

I plan to expand the range of my work to include other types of objects and creativity. Currently, I’ve begun a series of eight books about the French letter “H,” the Minotaur of the French language. It’s a character I created. The character’s head consists of fingers folded into what is called the “Minotaur” gesture. Thoughts about the French letter “H” came during the pandemic. Words like “Homme” (Man) and “Honneur” (Honor) begin with “H,” yet the letter is never pronounced; it leads to a somewhat dishonorable and inhuman existence.

I believe the letter is a perpetual prisoner of the French language, and today, its status needs to be reconsidered, as we all know what it’s like to exist in confinement. Can that even be called life?

In my graphics, I depict the letter “H” as the Minotaur character in various spaces, free of boundaries, full of freedom and joy. With a smile on its face, the character gains a free spirit and, finally, a sort of visa—the right to exist in any space without borders and rules, in the vibrant colors of life, with positive impressions after a long struggle for rights, for peace, for freedom.